----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Gideon Algernon Mantell was a county doctor with a practice in his hometown of Lewes, Sussex, where he was born in 1790. He was an excellent surgeon and midwife...at a time when up to 1 in 30 women died in childbirth in hospitals, Mantell lost only 2 patients in over 2000 births.

He was also passionate about the infant science of geology, having collected rocks and fossils from local quarries since he was a boy. At this time geology really was a very new science: it was only in 1654 that Archbishop Ussher used the chronology of the bible to date the creation of the world to the night before 23rd Oct 4004BC, and this was for at least the next hundred years the prevailing view. It was only in the late 18th/early 19th century that people really began studying the rock strata, and realising that they must have taken much more than 6000 years to form (although they had no way of dating the rocks at all, since carbon dating wouldn’t be discovered for a couple of hundred years!).

Mantell acquired a huge fossil collection, largely relying on local quarrymen, who he paid to provide him with material. But after the publication of his first book on the Geology of Sussex word started to get around of the fabulous bones to be found in the Tilgate Forest quarries, and he suddenly had competition for specimens. He was much vexed when a local amateur collector began outbidding him for fossils, writing in his journal, “…Drove to Cuckfield, and endeavoured to obtain some fossils from the quarrymen who have been employed by me so many years; but the ungrateful scoundrels refused to let me have one, having found a customer on the spot…It is after all a very cruel affair: when there are thousands of quarries in England which would be equally productive and interesting if persons would but take the trouble to explore them, I must be robbed of the fruits of my industry and trouble!...”.

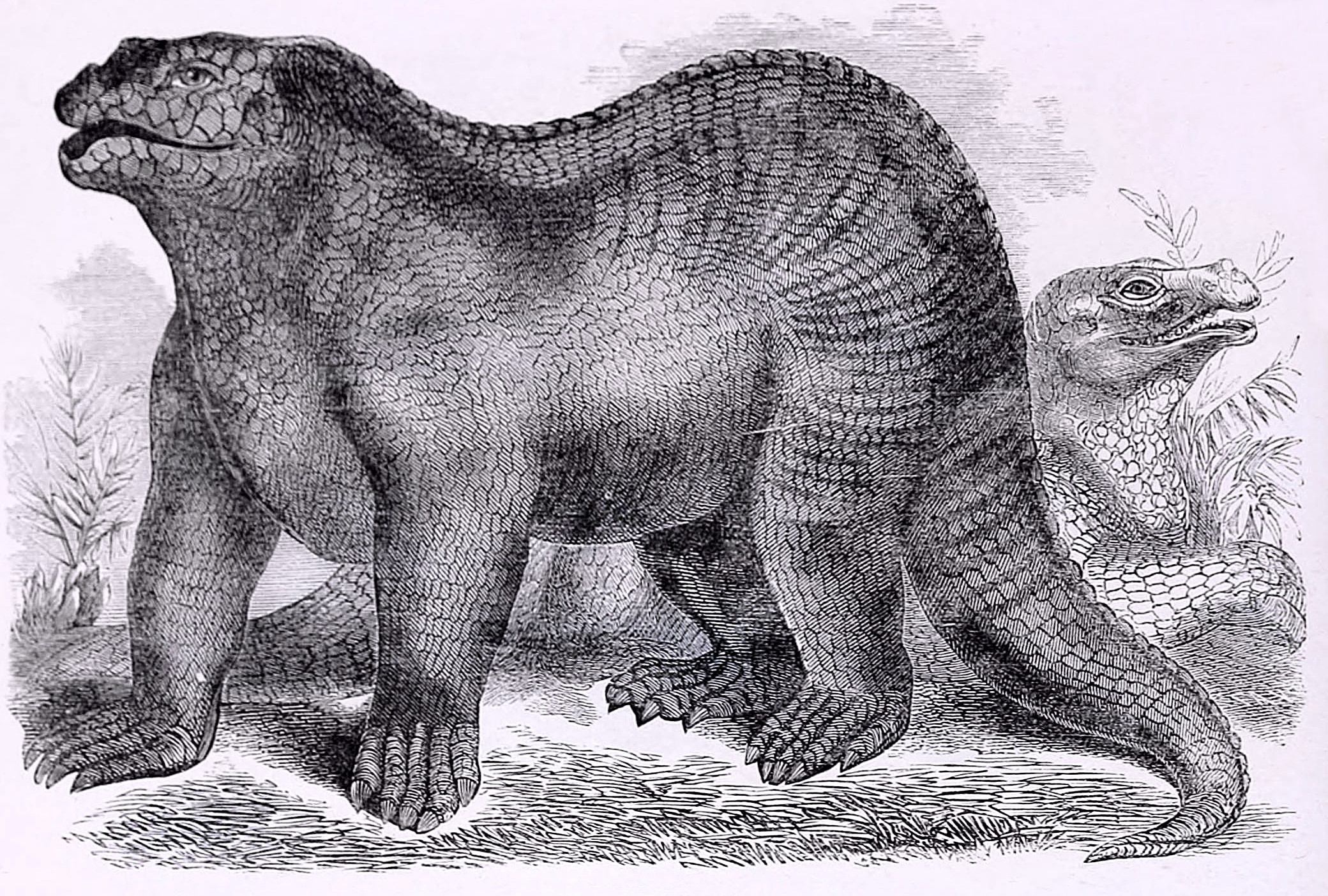

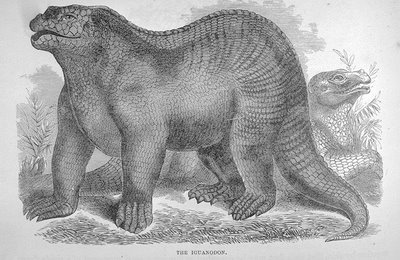

For many years Mantell was a successful doctor but a struggling amateur geologist; even after the publication of his first book he still struggled to gain recognition from the big names in the field. But amongst his collection he had pieces of bone from impossibly large extinct creatures, which he correctly recognised as reptiles. He took a tooth of one of these creatures to the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. The curator there showed him an iguana that had recently been brought back from the West Indies, and Mantell was impressed with how similar in form the teeth were. The creature was named Iguanodon (meaning ‘iguana tooth’). As it happens, the comparison with iguanas was rather oversold, as the teeth are actually only very superficially similar (as the anatomist Richard Owen took great pleasure in pointing out some years later). But because of the name, at the time Iguanodon was reconstructed to look very much like a giant iguana (see below. Note that the limbs are correctly positioned underneath the body rather than splayed out like a crocodile, although despite the fact that Mantell noted that the forelimbs were shorter than the hindlimbs, this was not reflected in most reconstructions of his time. Also you’ll note the horn on its nose, which is now known to be a thumb spike. And yes, I know I've used this picture in my blog before. But I like it).

Iguanodon was only the second giant reptile to be discovered; the first was described by William Buckland (an eminent geologist) in 1824 and named Megalosaurus. Mantell only very narrowly missed out on naming the first dinosaur...Buckland had been sitting on a specimen of Megalosaurus at the Ashmolean Museum for some years, afraid to publish a ‘giant reptile’ for fear of ridicule, but Mantell’s discoveries spurred him into action and he rushed out a paper shortly before Mantell published his Iguanodon. Of course, when first described Iguanodon and Megalosaurus were not called dinosaurs, because that term hadn’t been invented yet. It wasn’t until 1842 that the term ‘dinosaur’ was coined by Richard Owen.

The discovery of Iguanodon made Mantell’s name as scientist, and he was admitted to the Royal Society on Dec 22nd 1825. He was very proud of this, writing in his journal “This day I went to London, and at 8 in the evening attended at Somerset House to be admitted a Fellow of the Royal Society...It is with no small degree of pleasure that I placed my name in the Charter book, which contained that of Sir Isaac Newton and so many eminent characters”.

Mantell later discovered the bones of other dinosaurs: the primitive ankylosaur Hylaeosaurus, stegosaur Regnosaurus (known only from jaw fragment discovered by Mantell, pelvic fragment from Isle of Wight), and sauropod Pelorosaurus (a genus with a very confused history, having been given many names by many different people over the years!). He also collected many other fossils including plants, turtles, and ammonites.

Mantell moved his family to fashionable Brighton in the 1830’s, hoping to find a patron who would provide money for further collecting and research. He now had recognition as a scientist, but had yet to make any money from it. He turned his house into a museum, which was made a Scientific Institution and opened to the public in 1836. But it was a commercial failure (partly because Mantell would often kindly waive the entrance fee), and the museum bankrupted him. It was closed only 2 years after it opened, and Mantell was forced to sell his entire collection to the British Museum for the paltry sum of £4000. After everything was moved to the BM, only Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus were put on display, to Mantell’s great disappointment.

The whole business of setting up a museum in their home, and then having it fail, was very stressful for his whole family, and it put a huge strain on Mantell’s marriage. Fed up of Gideon putting science above her needs, his wife finally left him in 1839.

Mantell spent the last decade of his life in a state of severe ill health. He thought he had a tumour on the spine caused by many years spent stooping over patients, but he in fact suffered from severe scoliosis (curvature of the spine), which left him partially paralysed, and may have been caused by a carriage accident in 1841. He continued to work during this time, visiting patients, conducting research, writing papers and books and giving lectures when he was well enough, but he was in constant pain, taking laudanum, aconite, ether, chloroform, opium etc. frequently (and often at the same time!) as painkillers. He died in 1852 of an opium overdose. At time of his death, Mantell was credited with the discovery of 4 out of 5 then known genera of dinosaur. After he died a portion of his curved spine was removed by Richard Owen and kept at Royal College of Surgeons (until 1969, when it was destroyed due to lack of space).

These days Gideon Mantell’s name is one that commands great respect among palaeontological and geological circles, but he went without the recognition he deserved for many years, both before and after his death, due at least in part to a vicious smear campaign by a rival of his, the much more famous Richard Owen (a superb anatomist known mainly as the founder of the Natural History Museum in London, and for overseeing the building of the dinosaur models in Crystal Palace Park (a commission originally offered to Mantell, who turned it down due to ill health). If you’ve seen these fantastic models, you’ll know they’re hilariously inaccurate, but they were the best guesses based on the fossils that had been found at the time. They’re also now grade I listed buildings!).

Richard Owen was a very ambitious man, who was determined to be the most famous name in palaeontology. He had no qualms about sabotaging the careers of others to make this happen, and Mantell was just one of his victims. After Mantell’s death, an obituary was published in which he was rubbished as a poor scientist with an overinflated ego, and in which the discovery of Iguanodon was completely taken away from him and attributed to several other scientists, including Richard Owen. It was published anonymously, but it was widely believed to be the handiwork of Owen, an attempt to bury Mantell’s reputation with him.

Owen’s ruthlessness eventually caught up with him, though, and he was denied the presidency of the Royal Society due to his ill-treatment of Mantell over the years, and was eventually voted off the councils of the Royal and Zoological societies, and the Royal College of Surgeons, over other scandals (including stealing other people’s work and publishing it as his own). In later years he was overtaken scientifically, as evolutionary theory developed and his ideas became outdated. Even the Natural History Museum, built as a temple to the wonders of God’s creation, was hijacked by Darwin and his bulldog Huxley, and it has become a temple to evolution.