A departure from museums today, to discuss an interesting article I found today in New Scientist about wolves.

It shows that the idea of a 'pack heirarchy', with a strict pecking order and constant inter-pack competition for resources, is now a very outdated one. It was about 30 years ago that David Mech started publishing papers about the dynamics of natural wolf packs (made up of a breeding pair and their offspring) and how they differ from unnatural packs (made up of several unrelated individuals). You find unnatural packs in areas where wolf hunting is still allowed, as family groups are torn apart and surviving members are forced into coalitions with unrelated wolves in order to hunt. In these groups there is much more competition for food and resources than there is in a family group, because there is much less incentive for cooperation. Sadly, this is now starting to happen in areas that were previously protected, as hunting bans on the borders of National Parks are repealed (including Yellowstone, resulting in the destruction of at least one long-standing and well-studied pack).

In natural packs, the 'dominance heirarchy' idea goes out of the window: a wolf pack made of a family group is more like you'd expect a family to be - the parents are in charge, keeping the children in line, and they are all more inclined to cooperate than argue because they are related. You no longer get the strict Alpha-Omega pack structure that was observed from earlier studies on unnatural packs. But even unnatural packs show how socially adaptable wolves are as a species: where hunting and habitat destruction has reduced population numbers of African Wild Dogs, they are now dying out because they need to live in large family groups to share hunting and puppy-care duties, but wolves are able to make almost any social situation work to their advantage, at least in the short term, and are not so dependent on group living.

It is interesting that family dynamics affect not just inter-pack relationships and behaviour, but also affects the local ecology: in areas where wolves are not hunted and packs are made of family groups, wolves will take bigger prey (including moose), because youngsters are able to learn from their parents the valuable hunting techniques needed, and pack sizes tend to be larger. They also promote diveristy: in areas with intact natural wolf packs you see more songbirds, wildflowers, beavers and amphibians, because they keep down the numbers of large grazers.

A few years ago there was talk of reintroducing wolves to the UK (they were wiped out here in the 18th Century), somewhere in the Highlands of Scotland where they're out of the way of most people and livestock, but it doesn't seem to have gotten any further than talk yet. Which is a shame, because studies showed that wolf reintroduction could have conservation benefits by naturally controlling red deer populations. And I for one would love to hear the sound of wolf howls ringing out over the mountains!

(Hopefully) Exciting And Entertaining Excursions Into The World of Museums (And Natural History)

Friday, 25 June 2010

Wednesday, 16 June 2010

Things I've learned working in a museum (part VI)

That public speaking can be fun...

Which is something you'd not have heard me say a few years ago. Public speaking has always been a major phobia of mine. When I was a child, speaking at all was difficult! I was a painfully shy, incredibly frustrating child! I'm still incredibly frustrating to talk to because of my incredible indecisiveness and over-politeness, but that's another issue entirely. The speaking has become easier. A lot of it is just to do with growing up, and some of it is down to practice. Which is occasionally forced upon me, and sometimes done by choice (I'm such a sado-masochist!).

And this week I gave a public talk by choice! The 10 Minute Talk programme at the museum is really nice - it's a short length of time to have to speak for, the audience is usually small, with a smattering of regulars and curators who are there most weeks, so it's a nice safe little environment with not too much chance of embarrassment! The most wonderful thing about giving talks at work is that you are entirely free to talk about whatever you want, rather than having a topic forced upon you, which gives quite a lot of freedom and also allows you to talk about something you're really interested in, and that makes it a much more enjoyable experience all round!

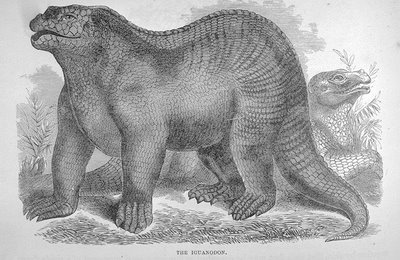

So this week I talked about Gideon Mantell (one of the first real pioneers of palaeontology, and the discoverer of 4 dinosaur species (although two of them are a little dubious these days!)). And I picked out some dinosaur material from our collections to pass round for people to have a good look at (we have some dinosaur material that came from Thomas Brown, a big collector of rocks and fossils, who Mantell exchanged material with over the years. I found some nice Iguanodon and Megalosaurus teeth and limb bone fragments). I had lots of pictures of fantastic 19th Century reconstructions of dinosaurs, like this one (love the dopey expression!):

Which is something you'd not have heard me say a few years ago. Public speaking has always been a major phobia of mine. When I was a child, speaking at all was difficult! I was a painfully shy, incredibly frustrating child! I'm still incredibly frustrating to talk to because of my incredible indecisiveness and over-politeness, but that's another issue entirely. The speaking has become easier. A lot of it is just to do with growing up, and some of it is down to practice. Which is occasionally forced upon me, and sometimes done by choice (I'm such a sado-masochist!).

And this week I gave a public talk by choice! The 10 Minute Talk programme at the museum is really nice - it's a short length of time to have to speak for, the audience is usually small, with a smattering of regulars and curators who are there most weeks, so it's a nice safe little environment with not too much chance of embarrassment! The most wonderful thing about giving talks at work is that you are entirely free to talk about whatever you want, rather than having a topic forced upon you, which gives quite a lot of freedom and also allows you to talk about something you're really interested in, and that makes it a much more enjoyable experience all round!

So this week I talked about Gideon Mantell (one of the first real pioneers of palaeontology, and the discoverer of 4 dinosaur species (although two of them are a little dubious these days!)). And I picked out some dinosaur material from our collections to pass round for people to have a good look at (we have some dinosaur material that came from Thomas Brown, a big collector of rocks and fossils, who Mantell exchanged material with over the years. I found some nice Iguanodon and Megalosaurus teeth and limb bone fragments). I had lots of pictures of fantastic 19th Century reconstructions of dinosaurs, like this one (love the dopey expression!):

and I regaled the people with a couple of quotes from Mantell's own journal, which I found on a shelf at our store building, and which started this whole 'wouldn't it be fun to do a talk about Mantell' idea. It's a great read. Between the musings about the weather and lengthly discourses on political matters, it has some fantastic entries, including "Today I saw the exhibition of a learned pig!" and other such gems. Which I didn't actually use, because it was pretty irrelevant! Unfortunately it's a hard book to get hold of, because it had a really limited run when it was published in 1940, and I don't think it's ever been republished.

And I think the talk went well. Everyone said they really enjoyed it, and they didn't look like they were just being polite...and I enjoyed it, which is probably the best indicator that it went well! My hands were visibly shaking a little as I was holding my pictures up, and I was a bit nervous, but in a good way. Not in an overwhelming 'aaarrrgh I can't function' kind of way like when I was younger. I am finally taming the beast! Public speaking still scares me, but it's no longer the horrendous torture that it used to be. And sometimes it can even be...fun! Who knew?

And I think the talk went well. Everyone said they really enjoyed it, and they didn't look like they were just being polite...and I enjoyed it, which is probably the best indicator that it went well! My hands were visibly shaking a little as I was holding my pictures up, and I was a bit nervous, but in a good way. Not in an overwhelming 'aaarrrgh I can't function' kind of way like when I was younger. I am finally taming the beast! Public speaking still scares me, but it's no longer the horrendous torture that it used to be. And sometimes it can even be...fun! Who knew?

Sunday, 13 June 2010

Things I've learned working in a museum (part V)

That's it's not a job for the faint-hearted...

I've spent some time recently in the Zoology department, effectively volunteering one day a week (but getting paid for it!) to get some experience and help out. And this is what I've been doing (some of the time, anyway):

I've spent some time recently in the Zoology department, effectively volunteering one day a week (but getting paid for it!) to get some experience and help out. And this is what I've been doing (some of the time, anyway):

Pinning insects. Which, when you get past the grossness of the idea of jabbing pins into dead animals, is actually quite fun. Well, as much fun as jabbing pins into dead animals can be! It takes a fair amount of skill, especially with the smaller beetles (some of which have incredibly tough exoskeletons, and getting the thin wobbly pins through their elytra without pinging them across the room is quite a challenge!). You also get to study the insects under a microscope, which is quite fascinating. Live insects I've really never been a fan of, but dead ones are actually quite beautiful. I had a little freak-out when the first insect I had a go at (one of the locusts) moved when I gingerly tried to stab it through the head (well, the thorax really), but after that I was fine. It becomes a mechanical process, and the hands work away without the brain having to think about what it is you're really doing! Which is not really that disgusting anyway. And as the curator pointed out, they've been dead a long time, so they're not exactly going to feel it!

The basic process is really quite simple:

You have a load of pitfall-trapped insects in a tube of alcohol, you tip it out into a petri dish, choose an insect, dry it off, and stick a pin through its thorax (or elytron if it's a beetle) just to the right of the middle line (so as not to destroy characters that are useful in distinguishing between species). Easy. Except that (as previously mentioned) some of the beetles are a bit of a bugger, and if you get the pin too close to the middle then the wing cases won't sit closed and it looks rubbish. Which I managed to do a few times, but not too many.

I also got to glue the heads back onto a couple of beetles, which was also pretty challenging, mostly because they were so damn small! And getting the head to go back on the right way up is not easy.

I'm told there are some wet-preserved mammal and fish specimens in the department that are going rather unpleasant and need to be decanted and disposed of as well. Can't wait! Mmm, I love the smell of formalin in the morning!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)